- Home

- R J Barker

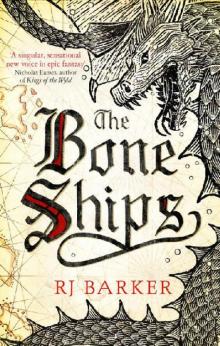

The Bone Ships Page 4

The Bone Ships Read online

Page 4

“Yes?”

“You address me as Shipwife, Deckkeeper.” The hardness back.

“Yes, Shipwife.”

“Before they condemned you, Joron Twiner, how long did you say had you been in the Hundred Isles fleet?”

“I had not, Shipwife.”

“Not even for a day?”

“No. Shipwife, not even for a day.”

He could almost hear her confusion, her wondering what strange circumstance had led to him being here, shipwife of a black ship at nineteen years old, and not lain in the sea with his veins open, hoping he bled out before the creatures of the deep found him. But she did not ask, and when she said no more he took his leave, out of the light of the great cabin and into the darkness of the underdeck. All along the deck glowed wanelights, the skulls of kivelly birds filled with skyfish oil, which let out a dim light, glowing through bone.

Shipwife, deckkeeper, deckholder, courser and windtalker, all had their own cabins next to each other in the rear of the ship, though he had only ever seen the inside of the great cabin. The courser and the windtalker made him uneasy in different ways and he found it best to avoid them, and the deckkeeper’s cabin had belonged to Barlay, who frightened him with her size and potential for violence. He knocked on the courser’s door, then silently cursed himself to the Northstorm for it. A deckkeeper had no need to knock; he was the shipwife’s hand and could go where he wanted.

“Enter.” Their voice soft. He entered, finding the courser sitting on their bed, dirty white robes pooled around them and the cabin filled with a sweet-smelling incense that failed to keep the general stink of the ship at bay.

“The shipwife wishes to see you in her cabin,” he said. Joron could not see their face under the hood of their robe. He wondered at the sudden curiosity that filled him, the desire to pull the hood back and find out whether they appeared male or female. Would he even be able to tell? But he did nothing, only stood, staring ahead like a new recruit desperate to avoid the eyes of an officer.

“Me?” said the courser. “But I have no charts.” Was there an edge there? Blame? There should be, but he found the courser’s soft voice as impossible to read as the strange whirling sigils and signs drawn on the walls of their cabin that talked of the great storms that ringed the world.

“The shipwife says bring charcoal and draw on the floor.”

“Well,” said the courser, “if the shipwife wants, I shall obey.” The courser levered themselves off the bed and carefully put out the incense burner – fire was always a worry. Bone may not burn easily but the glue used to fuse boneships together was flammable. The slight figure brushed past Joron, and he wondered what someone so unassuming could possibly have done to have found themselves among the condemned. He touched the birdfoot he kept strung around his neck, taking a little solace from the rough scales and sharp talons while whispering a few syllables to the Sea Hag, in hope of redemption when he stood in front of the bonepyre deep below the water.

He left the cabin and closed the door. On the way down into the belly of the ship he passed Cwell, as small as the courser but far more dangerous. She watched him with bright eyes from under her mop of stringy grey hair.

“You made a mistake, letting Meas on board, boy,” she said. “We’ll not have a moment’s peace now with her on deck, mark my words. You wait, a knife’ll find her despite what she says, and then it may find you.”

“I am deckkeeper.” He meant the words to have authority but made made them sound like a guilty secret, or an apology.

“Aye, so you seem to think.” She pushed herself up on the stairs so her body was against the ceiling, like an insect, and he could pass under her. Though he did not look up he could feel her eyes burning through him as he made his way into the hold to check the supplies.

The smell of rotting bone was stronger here. Tide Child needed the attention of the bonewrights, but half the ships in the fleet did and a ship of the dead would always be at the back of the queue. Tide Child was no white and shining main-ship, corpselights burning proud above him.

Behind the smell of rotting bone was the smell of human urine; no doubt some had relieved themselves here in drunken stupors. He tried not to think about what his bare feet were treading on, wading through, concentrating instead on counting the water pots, huge and square, checking the beads on them to see their levels. Enough water for a few days, but not much more. Less food, but fish could always be fought for their flesh if they were desperate. Any decent-sized ship attracted beakwyrm, and one of them would feed a crew, though they took some killing – and killed in turn if given the chance. Further on were pots of hagspit, distilled and mixed with powders by the bonemasters, a viscous oil that could be launched in the wingbolts. It burned hot enough to melt bone and flesh and could not be put out by water. They did not have much of it, but he did not imagine they would need it. Besides, he did not trust the crew not to spill it. That would be more dangerous to Tide Child than any enemy so he dragged two of the huge water pots over to hide the hagspit vats. Satisfied with this, he decided that what they had here would do for them, and he was glad, because he had no doubt that they would be getting under way quickly. Meas had a shine in her eye, a purpose, and he wondered how he could tell her that if it was fighting she was after it was too soon. That if she intended action she did not have the crew for it. They were cliquey, little groups all holding their own resentments close, and if they were expected to work the gallowbows, well, had they ever worked the gallowbows ?

But would she listen to him? He doubted it.

He made his way back to the great cabin through a ship full of unfamiliar industry.

With every squeak of mop on slate, rumbling of barrel across bone or voice singing out in rhythmic song as its owner pulled on a rope or turned a wheel, his resentment grew. How could she make this happen and he could not? Was it simply true that, Berncast as he was, shameful child of a weak mother, he had no authority? His mother had died in childbirth, like many women did. And though Joron was one of the lucky few, to be born without blemish or missing limb, the blood flowing from her broken body had proved his mother’s line weak. Any opportunity for her son to advance and join the ranks of the Kept among the Hundred Isles powerful fled with her life.

Meas though? She was born to the most prolific of the island’s leaders. Her mother had survived thirteen births and now ruled the Hundred Isles with all the hagfavour that gave her. Was it that strong blood that gave Meas some inherent power over others that he would always lack? Or was it simply that she had been brought up in the huge bothies of the fleet? Trained among the spiral stones, the vine-wrapped domes which reached up for the skies, their rounded bases covered in myriad bright paints, splashed upon the rocks to beg the favours of the Sea Hag, Mother or Maiden? Fisher boys with dead mothers never got invited to the spiral bothies; they signed on, at best to furl the wings and climb the rigging, to pull ropes and spin gallowbow wheels – and to die of course. They signed on to die. If they were very lucky they made purseholder or wingmaster or oarturner before they died, but they would never tread the rump of the ship without invite, for that was for those children of the Hag-favoured, the Bern and the Kept.

Yet he was here. And it seemed he would still be here and he would still wear the hat of a commander, though he could not for the life of him work out why. He could not be the only one aboard who knew numbers, he was sure of that.

Did he want to know why?

The desk in the great cabin had been pushed out of its comfortable rut and back against the wall. The white floor was marred with scrawled black lines and symbols that Joron knew well, though it took a moment for him to realise from where, so out of place were they. For that moment of wondering Meas ignored him, lost in the lines on the floor as the courser muttered to themselves and scrawled more symbols, added a long line with the burned end of a stick, finishing it with a flourish just as the familiarity slotted home in Joron’s mind like a boneboard into a joint.

/> It was a chart, unfamiliar because it was so big – it covered the entire cabin floor – and because it was not on birdskin and because it was inaccurate: bays and inlets he knew well were shown as smooth spaces and many coastlines of the Hundred Isles had been allowed to peter out, plainly because they were not on the course they were to take. The symbols and numbers the courser was jotting down twisted in his head, painting another line, one that twisted across the bones of the floor but only in the eye of his mind: the route Lucky Meas intended to take Tide Child on, sailing through the Archipelago, between isles and through channels until it terminated at Corfynhulme, a day and a half’s sailing away – if the Eaststorm was kind.

“Baffinly Channel was blocked in a landslide.” Joron said it without thinking because he knew it, had heard it said in some tavern on the mainland where life was still and did not constantly rock. The courser’s burned twig stopped in its track across the white floor; they raised their hidden head to Meas and the Shipwife nodded, flicked her fingers in an irritated, affirmative motion. The courser went back to their calculations, carefully rubbing out a portion, recalculating the way and adding, he estimated, another four hours to the trip.

“How sings the wind?” said Meas.

Joron did not answer, unsure whether she addressed him or the courser for a moment.

“The air is still in the bay; the storms neither bless nor curse us here,” said the courser, voice not far above a whisper. “I see the clouds clip east on the horizon where the sun don’t burn ’em off, Shipwife. I hear no song of great storms. I hear only the melody of kind winds.”

Meas nodded.

“Ey, the ship don’t rock enough for it to be anything else. Joron, put out the flukeboat and get us towed out to the bell to pick up the gullaime. It can take us the rest of the way out till we find wind enough to fill the wings.”

“But it—” he began.

She had no intention of letting him finish.

“Obey orders, don’t make excuses.” Said without thinking, and giving him no recourse to argument. His hand touched the hilt of his curnow. She smiled, or at least her cold lips hinted at it, and that was enough for his hand to leave the hilt, and for him to turn and leave to carry out her demands on the warm light of the deck.

“I need,” he began, barely raising his voice above speaking, and the words remained unheard by the deckchilder, all busy on the slate. Cough. Regroup. Start again. “I need volunteers!” he shouted. None turned; all were suddenly busier with whatever tasks they had found themselves. “I said . . .” he shouted again. Now some turned, work slowing, unfriendly eyes focusing on him.

Barlay put down the shot she held with one hand, shot he would have struggled to hold with two, and came to him. “Twiner,” she said. “Why is she here?”

“I need a group to—”

“I said, why is she here, Twiner?” Barlay’s voice was full of threat, like the moment a spear sinks into a longthresh and all know the flukes of its tail are now certain to breach the water in murderous fury, but not who will die in the beast’s wrath, or on its teeth.

He opened his mouth to answer her. At the same moment she took a step back and bowed her head as if in respect. For him?

No. Of course not.

He turned, knowing what he would see, must see, her: Meas, standing at the hatch.

“Barlay,” she said, snaking out from the underdeck, “I am glad to see such enthusiasm from you.” Barlay nodded as if that was exactly what she had been feeling, and Meas approached, pulling on one of the fishskin tethers that held her crossbows to her coat. “Pick seven you trust and take our flukeboat to the fishing village.” She held out a piece of parchment. “Commandeer another boat, one big enough to take some strain, small enough to stow on deck if we need to, and with a wing if there is such a one.”

“They won’t like it, Shipwife,” said Barlay, still looking at the deck.

“That is why I send a woman the size of you,” said Meas, nodding at the parchment. “This letter promises that Bernshulme will give them the price of what we take, and as it is now the growing time they should have no trouble replacing their boat.” Joron wondered if she knew she lied, that even the simplest flukeboat took at least a month to make, and a month off the water was likely to leave a fisher family starving. He wondered if she cared. “Well,” said Meas, “get on then.” She turned, and a deckchild scurrying past stopped in his tracks, unable to meet her eye. “You,” she said, “get a catapult and start knocking the skeers off the wings of the ship. Kill a few and the rest will think twice before coming back.” The man nodded and scurried off once more. “Joron, return to my cabin,” she said. Her voice promised nothing good.

His heart fell to rest in his stomach, spreading a tide of sea-cold blood through his system as the skeers took off in a cloud of noise, protesting the great and mortal insult done to one of their number by a stone launched from a spinning cord.

From the light to the dark he followed her. The smell of the underdeck would not let him forget he lived among the dead, but in the bright cabin with the chart floor the light was better, even if the atmosphere was not. Meas ignored him, dragging her desk back into its rut and sitting behind it. On the desk was the onetail hat of the deckkeeper. Black material, folded up around a rounded crown, at the rear the material falling in a plaited rope to dangle down the wearer’s back.

“You do not ask for volunteers,” she said. “You are an officer of the fleet. You tell the deckchilder what to do and if they do not do it they are punished.” He opened his mouth but she gave him no leave to talk. “And I doubt not that you think you have no authority over them for you do not, not really, and never have had, and that is your fault and no other’s. But that time has passed, for now you hold my authority. So speak with it, Joron Twiner, and if I must crack a few heads for them to understand that you being weak does not mean that I am weak then I will do it. Do you understand?”

He nodded.

“Why?” That single syllable again, leaking from his mouth like water seeps into the bilges. Weak, she was right to recognise him as that.

“Because you know numbers,” she said.

“As do others.” These words snapped out, his confusion forgotten in annoyance, emotions warring inside him. Who was she to treat him this way? Who was he to let himself be treated so? That almost-smile crossed her face again. She stood, came around the desk and stood in front of him. Smaller than he was, but more comfortable in her skin than he would ever be, a fierce predator before prey.

“That crew chose you as shipwife, Joron Twiner, not just because they believe you weak – and that is a hard course you have set that you must, in time, find your own route through – but because you have no loyalty to any other and you gave no clique an advantage. I have seen such decisions before.” Her tone was almost jovial, and he relaxed, if only a little. Then, as if remembering herself, who she was, what she was, where she was, the storm came upon her and she picked up the deckkeeper’s hat from the desk and took a step closer to him. “They do not respect you, but no one owns you and you owe no one. They have played you like a fish on a line, Joron Twiner, but I have made you deckkeeper so you owe me now, you hear?” She lifted the hat, showed it to him and then placed it on his head. “You owe me, not them. I chose to let you live, and you owe me. You belong to Lucky Meas, and you’ll learn to work a ship and those aboard or they’ll scrag you one night and your sentence is then earned and carried out, Sea Hag have you. But I own you now, you hear?” He nodded. “I own you. Speak it.”

He did not want to but saw no way out.

“You own me.”

She stared into his face, examining the lines and ridges, staring into his eyes as if searching for something.

“I hoped there was a little fight in you, but maybe not. Now check these numbers on the floor. The courser seemed to know their way, but I would have the numbers checked again.” And she turned away, sitting at the desk and taking a small book from her

pocket, leafing through it and staring at each page as if it held all the world’s secrets. And maybe it did.

Joron wondered what they were.

With the numbers checked he returned to the deck as Barlay brought in the boats. The new one she had crewed with her people, and they rowed it hard, wing hanging loosely from the spine, towing their own boat behind.

“Get up front,” he shouted, then pointed to the two deck-childer nearest to him and spoke with Meas’s voice. “You and you, up to the beak, tie on the boats and then put together enough childer to pull the oars of them both.” They sneered at him and skulked away, but did as he asked and for a moment he felt almost like he was a real officer on a real ship. Past those he ordered, Cwell stood on the deck, looking at him. A pyramid of wingshot had collapsed and spilled across the deck, the nearest shot by his feet, and it was all he could do not to kneel and start to stack it again, stack it correctly as his father had taught him to do. But he could not do that, because that was not an officer’s job. When he glanced around there was no one near enough to call on to do it except Cwell, who stared so balefully at him. He turned away, starting to stoop as Lucky Meas appeared on deck, striding towards the rump and barely sparing him a glance, caught as he was between kneeling and standing. Though he had no doubt she noticed, no doubt at all.

The beak of a ship was always reaching for the future. The curling spines of bone along the rail and above the ribs of the ship pointed forward. Below the rail the skull of the long-dead arakeesian, eyeholes filled with green sea glass and boneglue, stared sightlessly forward. Below the eyes the beak, clad in metal, built to ram its way into other ships and through the waves, to cut a curling path of spray and foam, pointed out the ship’s course.

The Bone Ships

The Bone Ships